The economy has done well in 2023, with strong wages and exports, but restraining inflation poses a challenge ahead. Explore the dynamics at play.

Brazil’s economy has been surprisingly resilient this year. Inflation-adjusted wages continue to grow at a relatively rapid clip as consumer price growth slowed. More recently, the labor market has tightened, and consumer confidence has soared. As a result, consumer spending is growing at a respectable rate. Export growth has also been notably strong, thanks in part to an exceptionally strong soybean crop this year. Exports will likely retreat some, but the outlook for soybeans remains relatively positive, while closer ties with China should put a floor under exports. Pushing inflation lower will be more challenging from here. Higher oil prices have already reversed the declines in headline inflation. Plus, services inflation looks relatively sticky. A lack of improvement on the inflation front will likely restrain consumer spending as real wage growth and interest-rate cuts slow.

Consumers hold up

Brazilian consumer spending has held up well this year. Real private consumption grew at an annualized 3.8% in Q2.1 Data released so far for Q3 point to ongoing strength for household consumption. The services sector has held up particularly well as consumer preferences have shifted back toward services after the pandemic. For example, inflation-adjusted revenues for accommodations and food services rose by 5.8% from a year earlier in July.2 Demand for communications and information services has also held up well. Consumer demand for goods is growing more slowly than it is for services. Even so, the volume of retail sales was still up a respectable 2.4% from a year earlier in July despite a contraction in fuel sales.3

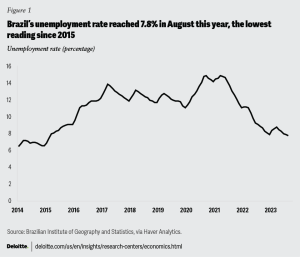

A relatively healthy labor market has contributed to the strength of the consumer. Minimum wage hikes and falling inflation are raising real wages. Inflation-adjusted wages were up 4.6% from a year earlier in August.4 At the same time, the labor market has tightened further. After dropping to 7.9% in December, the unemployment rate jumped up to 8.8% in March, raising concerns that Brazil’s recovery was reversing.5 However, the unemployment rate has since fallen to 7.8% in August, the lowest reading since 2015 (figure 1).

The improvements in real wage growth, inflation, and unemployment have raised consumer confidence as well. Consumer confidence has surged this year, reaching highs not seen since at least 2014.6 Despite the better outcomes for and outlook from consumers, household debt burdens remain high, suggesting that a pullback in borrowing is likely. At 28.3%, the household debt service ratio in June was the highest since data was first recorded in 2005.7 In July, the ratio came down slightly to 27.6% but remained firmly above prepandemic norms. About two-thirds of the increase in debt service is due to higher interest expenses, and so rate cuts from the central bank should eventually alleviate some of the stress.

Looking ahead, consumer spending is likely poised for a slowdown. For one, the strength in real wages is mostly due to inflation falling quickly. However, further declines in inflation will be more moderate. Indeed, headline inflation accelerated by 1.5 percentage points between June and August, which will push real wages lower.8 In addition, credit growth to the household sector is slowing very quickly, which bodes ill for consumer finances and spending. The rest of the economy will also likely slow, which will restrain hiring, real wage growth, and expenditures.

Additional disinflation will be more challenging

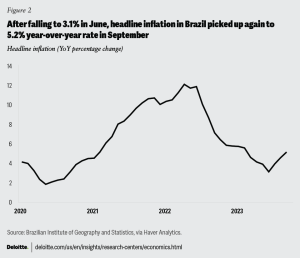

Brazil has made good progress in getting its inflation down. After peaking at 12% in April 2022, headline inflation fell to just 3.1% in June this year.9 Unfortunately, inflation has since picked up again to a 5.2% year-over-year rate in September (figure 2). Higher oil prices and base effects have caused the recent rise in inflation. Core inflation, which excludes food and energy, remained at 4.7% year over year in September, the same as August. Getting inflation to turn significantly lower will likely prove more difficult.

Goods inflation has also come down. For example, the price of food and beverages was up just 0.9% from a year earlier in September. The price of housing goods was down 0.2% over the same period. Meanwhile, services inflation continues to run hot. Health services inflation is in the double digits, while inflation for education, personal services, and recreation services was up more than 5%. Services inflation will likely be stickier as quickly rising labor costs could prevent further disinflation.10

In general, wage growth in the services sector is stronger than in the goods sector. In accommodation and food services industries, inflation-adjusted wages were 14.2% higher than a year ago.11 Given this strength in wages, it is little wonder that hotel prices were still up 12% year over year in September. As real wage growth continues to run hot in the service sectors, disinflation will be harder to come by.

The exchange rate presents another challenge in bringing inflation down. Brazil’s central bank has started to cut rates now that underlying inflation has moved considerably lower and is widely expected to make additional rate cuts over the next year.12 At the same time, central banks in the United States and Europe have become more hawkish and are widely expected to keep rates higher for longer. This divergence in expected rate paths between Brazil and the developed world is causing depreciation in the real. For the week ending October 6, the real depreciated to 5.14 per US dollar, an 8.5% depreciation from where it was just 10 weeks earlier.13

Brazil bucks the trade trend

Brazil’s exports have been surprisingly durable in the face of global headwinds. The most recent data shows that Brazil’s goods exports in US dollars were down just 0.3% from a year earlier. By comparison, they were down 9% in China, 7% in India, and 6.7% in South Africa.14 Weaker global demand for goods accompanied by lower commodity prices should have restrained exports in Brazil just as it did in other large emerging-market economies. Despite the resilience, we still expect exports to weaken in Brazil, though by less than what we see in the rest of the world.

A large part of the strength of Brazil’s exports has been due to a huge soybean crop. We expected the benefits of that crop to have ended by now, but agricultural exports were still up 16.4% in September, with oil seed exports, which include soybeans, up an astonishing 32%.15 The good news is that Brazilian soybean exports could have another strong year in 2024. Disappointing production in the US and ample demand from China point to such a scenario.16 However, even if Brazilian yields are high next year, the growth rate from the previous year is highly unlikely to look anything like the strong numbers seen this year.

The other main source of strength is the exports of mining products, which were up 9.4% from a year earlier.17 The recent rise in oil prices has helped to boost those exports. Given the recent volatility in oil prices amid conflict in the Middle East, it is difficult to predict where oil prices will go from here. However, relatively weak global demand and limited appetite for production cuts amid OPEC members suggests that oil prices are unlikely to break much higher in the near term. From a growth perspective, this will limit upward movement in this export category.

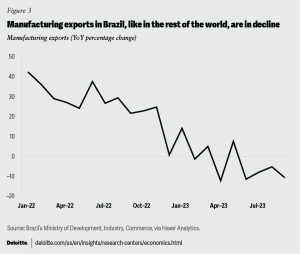

The largest major export category for Brazil is from the manufacturing industry. Depending on the year, these exports are typically about the same value as agricultural and mining exports combined. In September, those exports had fallen 10.6% from a year earlier (figure 3). This suggests that outside of commodity markets, Brazil’s exports are in decline, much like those in the rest of the world.

Weakening economic growth in China should have also hit Brazil’s exports. However, China’s imports from Brazil were up 8.8% from a year earlier in August, while they were down 8.9% for the rest of the world.18 This could be a change in the mix of goods demanded, but China’s imports of mineral products were up just 1.4% from a year earlier in August, while they were up 12.3% from Brazil alone.19 Brazil and China have deepened their trade relations, which may be helping Brazil to maintain higher export growth than its peers.20

Brazil’s economy faces some headwinds. Notable strength in consumer spending and exports are unlikely to be repeated next year as real wage growth slows and external demand wanes. Even so, Brazil’s economy can still move in the right direction. The central bank is lowering interest rates, which will support consumer finances. Meanwhile, the country’s export position may be better than previously thought. Assuming inflation continues to retreat, the economy can continue to grow through next year.

BY Michael Wolf

United States